Introduction

This is the second article in a series where I will rank the top ten Black baseball players at each position. I originally planned to include all ten individuals in one piece but based on the amount of information, I am splitting each position group into two parts.

Some of these lists will include active players, and you may be surprised by some of my additions and omissions. I hope to spark debate and discussion of Black baseball players of the past and present with my writing, especially by baseball fans who are a part of the African diaspora.

I will be including the careers of those who played in the Negro Leagues, Latin America, and the Caribbean before the integration of MLB. Black baseball players who have worn MLB uniforms will be included.

Because of the lack of statistical data for Negro Leagues players, firsthand and secondhand accounts will play a significant part in these rankings. Surface level and advanced statistics will be present, so I hope those who strongly prefer one or the other are satisfied with my assessments.

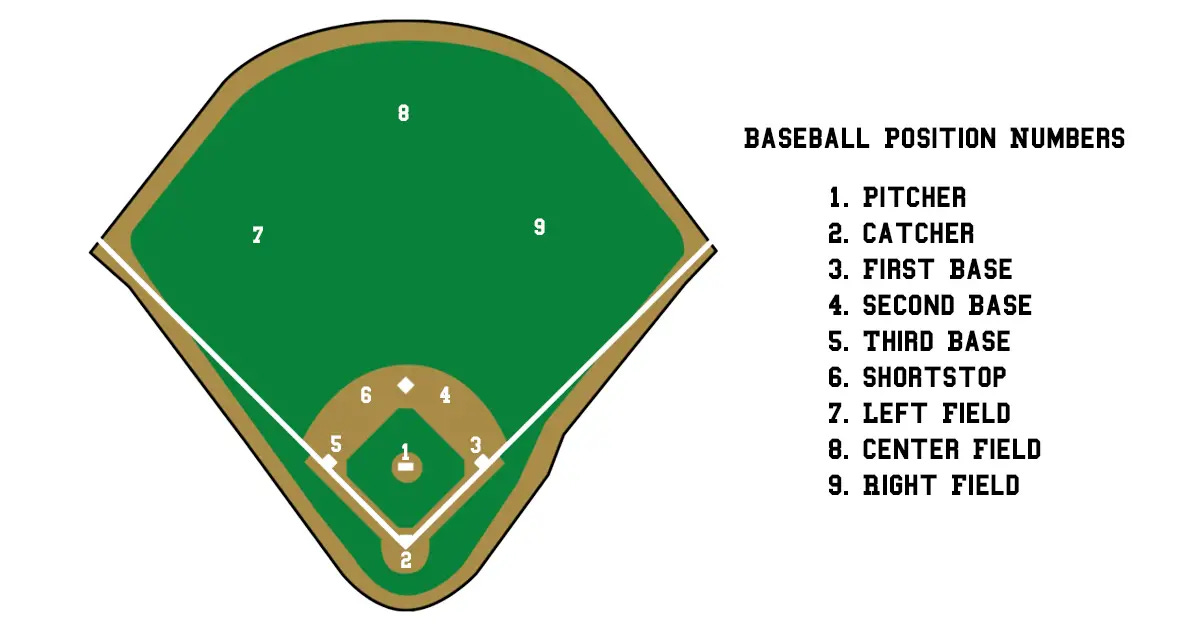

The position player rankings will be much more difficult but very rewarding and interesting, so I wanted to get those out of the way first. I will be starting with the catcher position and going in order based on each position's assigned number. There will be separate lists for Black starting pitchers and Black relievers, and those will be published last.

The Top Ten Black Catchers of All Time (#5 - #1)

Ranking my #1 - #5 for Black catchers was much easier than #6 - #10. Once I established the order I wanted to put the catchers in for the top five slots after I did my research, it didn’t change at all. I hope to catch some of you off guard with one of my inclusions for my top five Black catchers of all time. If I didn’t, then you must be as much of a sicko as I am. Starting with the top 10 Black catchers was fun and challenging. The top ten Black first and second basemen are next, which is going to be a doozy to figure out.

5. Russell Martin

"I'd been trying to convince the Dodgers for two years that they had a little Pudge Rodriguez on their hands. I don't know if he'll win ten Gold Gloves, but he has a chance to become that good. He's got a perfect body, sets a perfect target, and is really, really quiet back there." - Éric Gagné

Montreal, Quebec, Canada native Russell Martin put together a 14-year career with the Dodgers, Yankees, Pirates, and Blue Jays. He was a four-time All-Star who also won a Silver Slugger and Gold Glove one time each. He played in 58 postseason games across 17 series, helping every ball club he played for reach the playoffs as the primary catcher.

He was drafted in the 2000 MLB Draft in the 30th round by the Montreal Expos directly out of high school in Quebec but declined to sign. He was then drafted in the 17th round of the 2002 MLB Draft out of Chipola College, a JUCO in Florida by the Los Angeles Dodgers.

He started his professional career as a third baseman but was converted to a full-time catcher after his first season in the minor leagues. The Dodgers’ brain trust thought he had the makeup, intelligence, and athleticism to handle the position change and thrive behind the plate. Martin developed into a dynamic, five-tool catcher that could do a bit of everything on both sides of the ball during his time climbing through MiLB.

He had a 104 wRC+ for his MLB career, recording nine seasons above the 100 mark. Despite a career batting average of .248, Martin had above-average contact skills based on his 18% career strikeout rate. During his first five seasons, his strikeout rate never eclipsed 15%. His peak offensive season came with the Pirates in 2014, going .290/.402/.430 in 460 plate appearances across 111 games.

Drawing walks was a key part of his offensive profile, owning a .349 on-base percentage that was buoyed by an 11% walk rate and 0.65 walk-to-strikeout ratio for his career. His 792 walks are the 13th most by a catcher in MLB history. With 255 doubles, 191 home runs, and a career ISO of .148, Martin showed an ability to accrue extra-base hits at an above-average rate for a catcher. He hit at least 20 home runs in a season three times and hit at least 10 home runs in an additional 8 seasons.

Since 1920, he is one of only four catchers in MLB to steal at least 100 career bases and one of nine to swipe 20 bags in a single season. During the 2007 season, he came one home run away from becoming the second catcher to ever steal 20 bases and hit 20 home runs in the same season.

The strength of Martin’s game was his ability to defend, as he is one of the greatest defensive catchers of the 21st century. He was extremely durable, making at least l07 defensive appearances in 10 of his 14 seasons in MLB. His 1579 career games as a catcher are 27th all-time and the fourth most out of 233 catchers to log at least 1000 defensive innings during the 21st century.

He kept his passed ball total in the single digits in 13 of his 14 seasons, which shows that his ability to block pitches was above average. He allowed a lot of stolen bases during his career because of his mediocre pop times. Despite his 30% career caught-stealing percentage, he had years where he successfully controlled the running game at an above-average to plus rate.

The advanced metrics backup Martin’s case as one of the best defensive catchers of the 21st century. He is second in Defensive Runs Saved and first in Framing Runs out of 74 qualified catchers to have recorded at least 4000 defensive innings from 2000 - 2023 per FanGraphs.

All in all, Russell Martin is one of the greatest catchers who played most of his career during the 21st century. One of Canada’s greatest players and one of the best MLB draft picks from the 10th to 20th round range, he put together a borderline Hall of Fame career by being a durable jack of all trades.

4. Quincy Trouppe

“Quincy just came in a little too late because he couldn’t get in during his prime. It’s a shame because there’s no doubt in my mind he would have been a very good major leaguer if Black people had been allowed into the big leagues when he was in his prime.” - Bob Feller

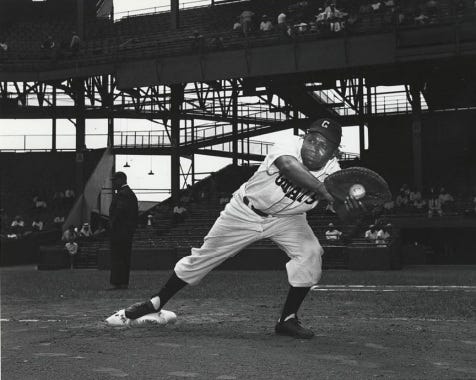

Quincy Trouppe collected 13 All-Star appearances during a 22-year career as a switch-hitting catcher and player-manager in the Negro Leagues and numerous winter leagues in the Caribbean, Central America, and South America. The youngest of 10 children, Trouppe spent the first decade of his life in Dublin, Georgia before moving to St. Louis, Missouri in the early 1920s. In a similar fashion to Jackie Robinson, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and other prolific Black baseball players, Trouppe could’ve been a professional athlete in a number of sports.

Standing 6’2’’ and weighing 225 pounds, he established himself as one of the best amateur fighters from the Midwest during his late teens. He had a prolific amateur boxing career, winning St. Louis’s first-ever Gold Gloves tournament. He almost quit playing baseball to become a professional heavyweight boxer but was talked out of it by Archie Moore, one of the greatest pound-for-pound boxers in the history of the sport.

He made his debut as a professional baseball player with the St. Louis Stars at 17 years old in 1930. He played for a variety of Negro League teams across the Midwest during the 1930s, establishing himself as the third-best catcher in the Negro Leagues behind Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey. An MLB scout once said that Trouppe was so good during the 1930s that if he was White he’d receive a six-figure signing bonus from an MLB team.

Trouppe was a pull-oriented hitter who was able to hit for average and power from both sides of the plate. He was very skilled at hitting breaking balls and routinely posted extremely impressive stat lines against top-tier competition throughout his two decades as a professional baseball player.

His reputation as a defender was stellar, described as one of the best behind the dish during his era. He was known as one of the best baseball minds of his generation. He was noted for his ability to handle a pitching staff and call games. Firsthand accounts labeled him as an above-average pitch blocker with a cannon for an arm.

Throughout the 1940s he was playing professional baseball year-round. He competed in the Negro Leagues and exhibition matches in the US and Canada during the Spring and Summer months while playing in Latin America and the Caribbean during the colder parts of the calendar. He began playing baseball in Latin America in 1939. By the end of the decade, he was a household name in Mexico, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, and Puerto Rico.

The professional baseball scene in Latin America and the Caribbean was crowded with talent from the mid-1930s to the early 1950s. The talent pool included Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella, Pedro Cepeda, Monte Irvin, Henry Aaron, Willie Mays, Roberto Clemente, Edward Green, Satchel Paige, Luis Tiant II, Martin Dihigo, and Josh Gibson.

Trouppe was called “El Roro”, Spanish for “The Baby”. It was similar to the “Babyface” moniker he was known by in the Negro Leagues. Another popular nickname for the switch-hitter was “The Big Train”. One story goes that Trouppe’s talents were so sought after that the Mexican League President Jorge Pasquel basically traded 40,000 factory workers for the catcher.

He got his first opportunity to be a manager while playing in the Mexican League during the early 1940s. He honed his skills and built a reputation as an excellent player-manager in Mexico and Puerto Rico’s winter leagues.

“He was one of the few managers that would fit in any era, now or in the past…He was a real gentleman. He was clean-cut, and well dressed. He was a model for the guys on the team. He never cussed. He might say “dawg gone.” I never played for a finer gentleman. And he knew the game – very well.” - Riley Stewart

He got his chance to be a player-manager in the Negro Leagues during the 1945 season for the Cleveland Buckeyes. He led the Buckeyes to two Negro Leagues World Series appearances, sweeping Josh Gibson and the Homestead Grays in 1945 before losing to Luis Tiant II and the New York Cubans in 1947.

Quincy Trouppe made his MLB debut during the 1952 season and while he only appeared in six games, he was the first African-American catcher to play in the American League. He played 84 games with Cleveland’s Triple-A affiliate during the 1952 season at age 39, going .259/.420/.429 with seven doubles, two triples, and eight home runs.

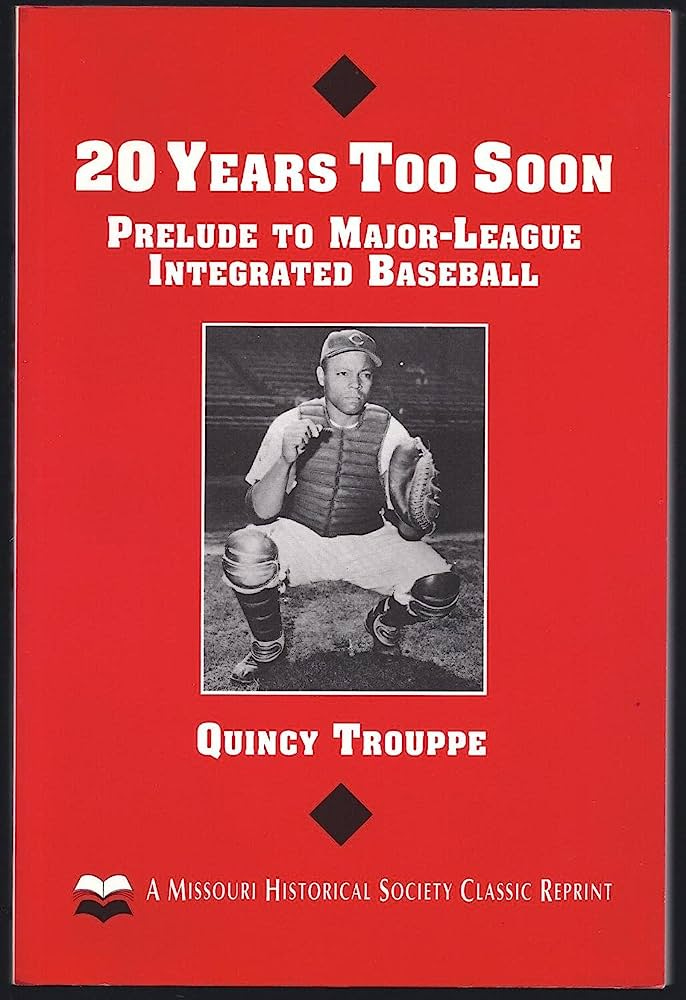

After retiring from playing during the mid-1950s, he became one of the first Black scouts for an MLB organization with the St. Louis Cardinals. He was also a noted historian of Negro League Baseball, compiling a vast archive of photos and film. He wrote an autobiography titled 20 Years Too Soon: The Prelude to Major League Integrated Baseball published in 1977.

3. Roy Campanella

"And Roy Campanella, certainly not the least of his mates, was all heart. The joy of the game, the love of baseball, was reflected in his every move. Stocky and compact, Campy was surprisingly swift on the basepaths and a stone wall protecting the plate. He was talkative. Campy would kibitz with the batters and the umpires. He was as masterful at banter as at handling pitchers, speaking to them not just with his mouth, but by pounding his fists, gesturing in every direction. The man loved what he did, and did it so well. One forgets, three times he was the National League's most valuable player. When Campy played well, so did the Dodgers." - Michael Berenaum

Born and raised in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania during The Great Depression, Roy Campanella made his debut as a professional baseball player at 15 years old. Only able to make appearances on the weekends because he was in high school, he was so sought after that he’d make more money playing in games on Saturday and Sunday than what his father made in a week.

At 16 years old he dropped out of high school to become a full-time professional baseball player with the Baltimore Elite Giants, backing up the legendary catcher/manager Biz Mackey. He was promoted to be the starting backstop at 17 years old and won an MVP Award in the Negro Leagues just two seasons later at 19 years old. By the time he was 20 years old, Campanella already had parts of five seasons under his belt as a professional baseball player and was challenging Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey for the title of the best catcher in the Negro Leagues.

Campanella signed with the Brooklyn Dodgers before the 1946 season. Only 24 years old, he had already accumulated nearly a decade of service time in the Negro Leagues and Latin American winter leagues. After two years in the minor leagues, he made his MLB debut in 1948 and quickly affirmed that he was the best catcher in MLB.

Between 1949 and 1957 Campanella was sixth in batting average, fourth in on-base percentage, and first in slugging out of 34 qualified catchers in MLB. He was second in total hits, singles, doubles, home runs, runs scored, and RBI, behind fellow catcher Yogi Berra of the New York Yankees. His peak offensive season was in 1953 when he slashed .312/.395/.611 with 41 home runs and 142 RBI. His .277/.361/.506 career slash line and 125 wRC+ would be stellar offensive production for a catcher in any era of baseball.

A right-handed batter, he worked with a swing that allowed him to loft the ball into the air at a high rate. This combined with his elite raw power made him one of the greatest power-hitting catchers in the history of professional baseball. He hit at least 20 home runs in seven of his ten MLB seasons, peaking at 41 home runs in 1953. He is tenth all-time for home runs hit by a catcher, owning a total of 260.

During his MLB career, Campanella made 100 defensive appearances in nine straight seasons, a testament to his durability. His 1364 games as a catcher are 48th all-time and his 57% caught-stealing rate is the best ever. He was extremely adept at controlling the running game because of his laser-esque throwing arm and elite athleticism behind the dish.

His two-decade baseball career was tragically cut short by a car accident that paralyzed him from the shoulders down during the winter after the 1957 season. He won three NL MVP Awards during his ten years in MLB because of his ability to dominate on both sides of the ball. He made five World Series appearances with the Dodgers during the 1950s, helping the ball club secure the 1955 World Series. While Roy Campanella isn’t the greatest Black catcher of all time, he’s definitely the best Black catcher to ever wear an MLB uniform.

2. Josh Gibson

“There is a catcher that any big league club would like to buy for $200,000. His name is Gibson. He can do everything. He hits the ball a mile. He catches so easy he might as well be in a rocking chair. Throws like a rifle. Too bad this Gibson is a colored fellow.” — Walter Johnson

Josh Gibson began playing professional baseball in the Greater Pittsburgh area at 16 years old and was a full-time player by the time he was 19. While there was a lot of debate about whether Gibson could handle a pitching staff and lead a ball club on a level of Biz Mackey, he quelled those concerns when he stepped into the batter’s box. Per Baseball Reference, Gibson’s career slash line in the Negro Leagues was a ridiculous .373/.458/.718!! During his time in the Negro Leagues Gibson was the second-highest-earning player after Satchel Paige.

Gibson was a slightly above-average receiver and framer with one of the strongest throwing arms in the history of baseball. Standing 6’1’’ and weighing around 230 pounds, he was extremely athletic and mobile for a catcher.

During his Negro Leagues career he only played for the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords, becoming a hometown hero in the city where he grew up. He won two Negro League World Series and two Negro League Triple Crowns in addition to a myriad of records.

Gibson dominated the winter leagues of Latin America, playing in Cuba, Venezuela, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico. He traveled to Cuba and Mexico the most, especially during the late 1930s and early 1940s. Many African-American players looked forward to playing in Latin America during the winter months because they didn’t have to deal with de jure and de facto racism and were typically paid at a very handsome rate.

The accounts of Gibson’s hitting prowess are simply absurd, as many state that he hit 500-foot home runs on a frequent basis. Former Negro Leagues player-manager Alonzo Boone said that: “Josh was a better power hitter than Babe Ruth, Ted Williams, or anybody else I’ve ever seen. Anything he touched was hit hard. He could power outside pitches to right field. Shortstops would move to left field when Josh came to the plate.”

Hall of Famer Monte Irvin said “I played with Willie Mays and against Henry Aaron. They were tremendous players but they were no Josh Gibson. He had an eye like Ted Williams and the power of Babe Ruth” Satchel Paige described Gibson as the “best hitter I’ve ever faced”. Cool Papa Bell said, “He hit line drives that just kept going.”

1. Biz Mackey

“Considered the master of defense, Mackey possessed all the tools necessary behind the plate. An expert handler of pitchers, he studied people. … He was a master at framing and funneling pitches. Pitchers recognized his generalship and liked to pitch to him.” - James Riley

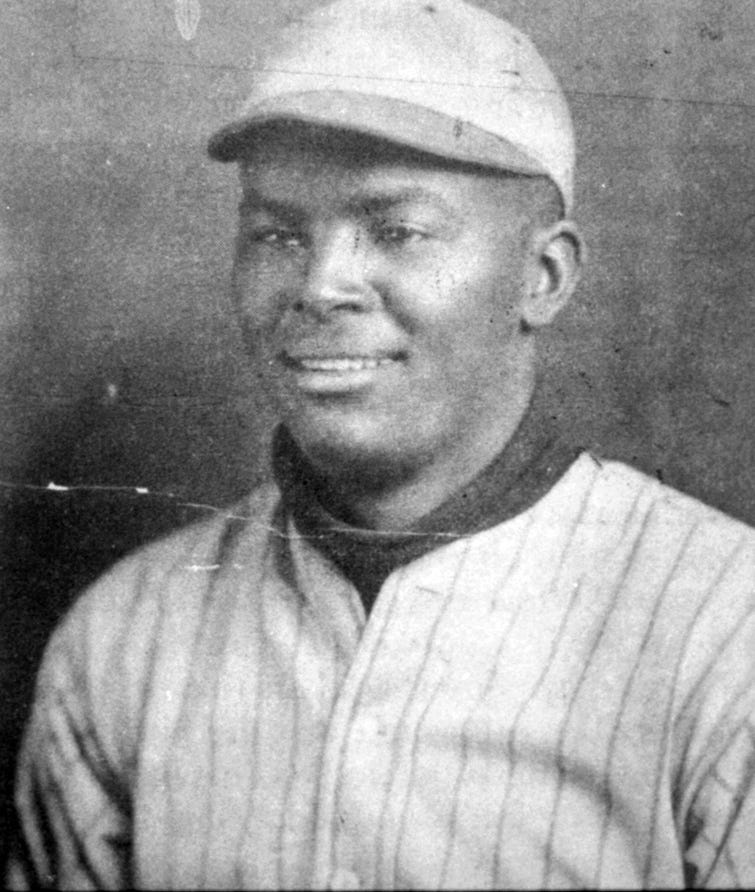

James “Biz” Mackey had a baseball career that lasted around thirty years, playing professionally before the Negro Leagues even existed during the late 1910s and retiring during the late 1940s as they slowly faded into obscurity because of MLB’s integration.

Mackey got his nickname because of his reputation for talking trash to hitters whenever he was behind the dish on catching duty. Known for “giving guys the business” as soon as they stepped in the batter’s box, this heavily contrasted the quiet and lowkey manner with which he conducted himself off the field.

He dominated the Negro Leagues’ early years as a super-utility player, playing every position on the field and pitching while being one of the best hitters to step foot in a batter’s box. He won two Negro Leagues World Series during his career as a player-manager, winning his first title in 1925 and winning his second over 20 years later in 1946.

Mackey is heavily credited as the greatest defensive catcher to ever play in the Negro Leagues. Pitchers raved about his capability to inspire confidence and handle a pitching staff. His peers behind the dish said that they learned everything about playing defense from watching Mackey work.

Mackey was renowned for his ability to develop young baseball players regardless of position. He worked with and played a huge part in the evolution of Don Newcombe, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Roy Campanella amongst many others into Hall-of-Fame caliber baseball players during their formative years in the Negro Leagues.

While the switch-hitting catcher wasn’t the hitter that Josh Gibson was he was awfully close while being eons better as a defender and manager. Mackey regularly batted in the high .300s, capturing a Negro Leagues Triple Crown and reaching the coveted .400 mark multiple times.

Many pundits and historians view Biz Mackey as the greatest catcher in Negro Leagues’ history, and it seems that it was the consensus amongst many individuals who saw Gibson and Mackey play. Cum Posey, the owner of the team Josh Gibson played for, thought Mackey was better than Gibson: “For combined hitting, thinking, throwing and physical endowment, there has never been another like Biz Mackey. A tremendous hitter, a fierce competitor … he is the standout among catchers.”

Explaining My List

I am quite sure many of you are surprised at the inclusion of Russell Martin. He’s definitely one of the most underrated position players whose entire career took place during the 21st century, and the numbers say so. Especially his defense.

Martin was pretty much a top 5 catcher in baseball from the very beginning of his career all the way until his final contract with Toronto during the mid-2010s. As the greatest Canadian catcher in baseball history and one of Canada’s greatest position players, I think he should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In defense of including Martin, a lot of baseball fans don’t know how to properly quantify good to great defense from a full-time catcher, especially when that catcher has the ability to be at least average offensively. It is one of the most complex and demanding jobs in all sports, both mentally and physically.

Catchers that have the ability and durability to be very productive on both sides of the ball for as long as Martin was are very rare. A lot of backstops who were worse than Martin at hitting and defending have gotten heaps of praise over the years. Just look at Salvador Perez’s career for example.

Quincy Trouppe is probably the most underrated Negro Leagues catcher ever, getting overshadowed by Double Duty Radcliffe, Josh Gibson, and Biz Mackey despite belonging in the same tier because of his comparable production during the same era of baseball. Posting an OPS over .800 in Triple-A at age 39 was no small feat and a clear indicator that he was an immensely talented baseball player. The firsthand accounts of his performance on the field from teammates, opponents, scouts, etc. line up with the tall tales and available statistics.

It is extremely difficult to put Roy Campanella’s dominance of the Negro Leagues and Latin American winter leagues during their competitive peak as a teenager and seamlessly continuing to dominate MLB during his 20s and 30s into words. I knew that Campy had to be the highest catcher to ever wear an MLB uniform on this list but I was wary about putting him over Trouppe. It made more sense to me after I sat and thought about the fact Campanella reached his prime earlier than the other nine catchers on this list and played a decade in the Negro Leagues and MLB where he was the second-best catcher at the minimum.

Josh Gibson and Biz Mackey were gonna be my one and two no matter what. I had Gibson first until I stumbled upon the owner of the Homestead Grays saying Mackey set the standard for catchers. Looking at the statistics and firsthand accounts, Mackey was much closer to Gibson in the batter’s box than Gibson was to Mackey with the glove or at managing a team.

The resumes of Gibson and Mackey speak for themselves. The inclusions of both don’t need as much elaboration as the other eight. What made me decide to put Mackey above Gibson was Mackey’s ability to manage and develop young players. He was an elite player who could play every position in addition to being one of the best managers and scouts of all time. He was a one-man front office that was also one of the greatest baseball players ever.

As usual Patrick i learned about great players id barely heard of. Thank you for shining a light on these hidden gems🙂👍⚾️

Very educational. Put a face to the names, as they say. I was shocked when I got to Josh Gibson at number two. But now I will have a new found reverence for Mackey!

This article leads me to a question I’ve wondered for a long time, and I would guess you might be able to answer definitively. The 1971 Pirates fielded the first all black lineup in MLB, as is annually written about. Every article and feature and blurb says the “first” all black lineup, but my contention is that it’s almost certainly the *only* all black lineup. (Obviously this was before the Negro Leagues were recognized as major leagues.)

To me, it all starts with a black catcher and pitcher, and then you go from there (ie. Dock pitching to Manny.) So I think of how many times did Charles Johnson or Russell Martin catch black pitchers, and in those instances was there any chance of the other seven guys being black. To me the answer is no.

But watch next year and all the articles will say “first” instead of “only”…