Discover more from The Red Black Green Baseball Blog

Introduction

This is the first article in a series where I will rank the top ten Black baseball players at each position. I originally planned to include all ten individuals in one piece but based on the amount of information, I am splitting each position group into two parts.

Some of these lists will include active players, and you may be surprised by some of my additions and omissions. I hope to spark debate and discussion of Black baseball players of the past and present with my writing, especially by baseball fans who are a part of the African diaspora.

I will be including the careers of those who played in the Negro Leagues, Latin America, and the Caribbean before the integration of MLB. Obviously, Black baseball players who have worn MLB uniforms will be included.

Because of the lack of statistical data for Negro Leagues players, firsthand and secondhand accounts will play a significant part in these rankings. Surface level and advanced statistics will be present, so I hope those who strongly prefer one or the other are satisfied with my assessments.

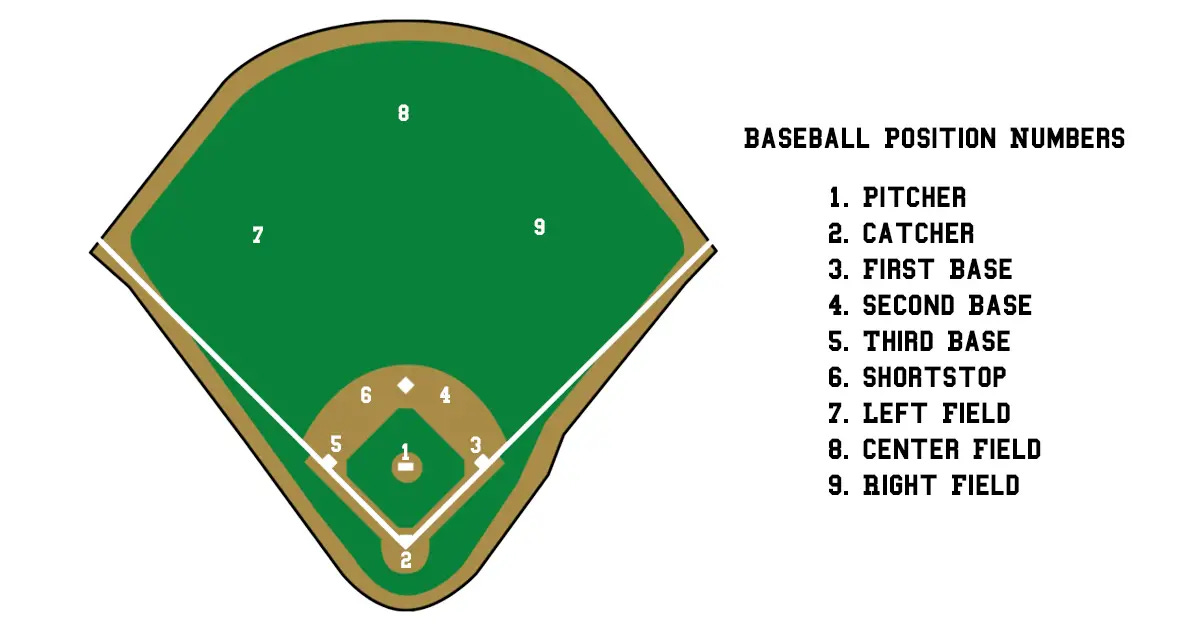

The position player rankings will be much more difficult but very rewarding and interesting, so I wanted to get those out of the way first. I will be starting with the catcher position and going in order based on each position's assigned number. There will be separate lists for Black starting pitchers and Black relievers, and those will be published last.

The Top Ten Black Catchers of All Time (#10 - #6)

When I initially thought about putting this list together, I expected a lot less Black talent at the catcher position. The ten catchers on these two lists are some of the most important players of their respective eras and leagues, molding baseball history with their actions in the batter’s box and behind the dish. A large majority of the catchers on this list have extensive postseason careers, with many of them winning the World Series of their respective leagues.

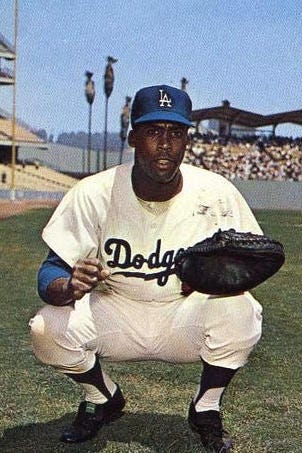

10. John Roseboro

John was about as flamboyant as Calvin Coolidge. John was the kind of guy whose shirt and socks matched. He hardly ever spoke above a whisper. He never came to camp in a pink Cadillac. No one linked his name with any movie stars. He hated parties. Heck, he couldn’t even dance. - Jim Murray

Born and raised in the small town of Ashland, Ohio, John Roseboro quietly put together a 14-year career. The catcher who said so few words he was known as “Gabby” in the Dodgers clubhouse is a constant figure in the franchise’s rich lore. He spent 11 seasons wearing Dodger Blue and has another three seasons under his belt with the Minnesota Twins and Washington Senators.

He is known for being at the center of the most infamous brawl in MLB history by getting hit over the head with a bat by Juan Marichal. He replaced Roy Campanella as the starting catcher for the Dodgers franchise after the future Hall of Famer was the victim of a car accident that paralyzed him from the shoulders down. He also made his MLB debut during the 1957 season, the final year of the Dodgers franchise calling Brooklyn home.

Roseboro was no slouch in the batter’s box, posting five seasons with a wRC+ above 100. Driving the ball for extra-base hits wasn’t his forte, logging only 338 extra-base hits during his career. Drawing walks was one of the strengths in his offensive profile, posting a double-digit walk rate in eight of his 14 seasons in MLB.

Despite only two Gold Gloves, he was a defensive stalwart. From 1957-1970 he caught more innings than any other catcher who caught at least 1000 innings behind the dish, leading the second-place Elston Howard by more than 2000 innings. Roseboro’s strengths were controlling the opposing team’s running game and game-calling.

A six-time All-Star and three-time World Series champion, he was a core piece of the Los Angeles Dodgers throughout the entire 1960s. He finished his career with a .249/.326/.371 slash line in 5529 plate appearances, tallying 1,206 total hits, 190 2Bs, 44 3Bs, and 104 HRs. His career wRC+ is 93 and his career OPS is .697.

9. Earl Battey

“Earl had two very important things going for him. He was a fun guy in the clubhouse. More importantly, he had everyone’s respect, because he had sore knees, sore hands, sore everything, but he stayed in the lineup. I didn’t realize how good of a catcher Earl was until he was gone.” - Harmon Killbrew

Los Angeles, California native Earl Battey was a five-time All-Star and won three Gold Glove awards during his 13-year career. He was signed by the Chicago White Sox directly out of high school and labeled as the best high school catcher in his class by pundits. He flew through the minors, making his MLB debut at 20 years old.

He spent his first five seasons as the backup catcher of the team on Chicago’s South Side, although calling him a part-time major leaguer was a stretch. He never logged more than 198 plate appearances in an individual season with the White Sox. He was traded from Chicago to the Washington Senators early in the 1960 season and got his chance to be a full-time player.

Battey played 137 games during the 1960 season, the last year the Washington Senators franchise would exist before moving to Minnesota and becoming the Twins. The 25-year-old went .270/.346/.427 with 24 doubles and 15 home runs. This was his first of six straight seasons with at least 125 defensive appearances behind the plate and an OPS higher than .740, which encapsulates his ability to perform on both sides of the ball. He was an above-average hitter who could hit for average and power. He possessed competent on-base skills, owning a .349 career on-base percentage and 0.90 walk-to-strikeout ratio.

He was one of the more productive defensive catchers of the 1960s, leading the AL in caught-stealing percentage twice. He was top 3 in the American League for the total amount of runners caught stealing in four different seasons. From 1960 to 1965 he was either first or second in defensive appearances as a catcher.

He was one the star players of a Minnesota Twins team that had four seasons with at least 90 wins between 1961 and 1967 and came one win away from making it five during the 1966 season. The Twins peaked during the 1965 season, where they won 102 games and lost the World Series in seven games to the Los Angeles Dodgers.

Battey was the leader of a clubhouse that included Harmon Killebrew, Zoilo Versailles, Tony Oliva, and a myriad of other talented players. He was bilingual, being able to speak Spanish as fluently as he could speak English. He built a close bond with his Latino teammates as the diversity in the clubhouse mirrored the diverse neighborhood in Los Angeles where he grew up.

The Californian was one of the most productive catchers of the 1960s though he was a full-time player for only half of the decade. He was battered by a myriad of injuries during the 1967 season that forced him to retire at just 32 years old. If Battey got the chance to play on a full-time basis during his early 20s and into his mid-30s, he would be much higher on this list.

8. Charles Johnson

“These are the hands of a surgeon, or maybe a pianist. The palms

are smooth, pink pillows of softness. The fingers are long and

straight. The nails extend well past the fingertips in the

clipped perfection that espresso-sipping European models in

Miami Beach's SoBe district would envy. Yet these are the hands

of...a catcher? That crash-test-dummy position that leaves the

fingers of those foolish enough to play it with more doglegs

than Augusta?Catch this: These are also the hands that happily cleaned the

house after school, that washed the dishes after dinner, that

survived point-blank poundings of fastballs shot from a backyard

pitching machine and that has become, as evidenced by an astonishing streak of flawless defense, the surest hands of any

catcher ever to play the game. These are the hands of Charles

Johnson, the 26-year-old Florida Marlins backstop who last made

an error when he was 24--so long ago that he cannot even

remember it. Not even Madonna looks this good in leather.” - Tom Verducci

Fort Pierce, Florida native Charles Johnson spent 12 years wearing an MLB uniform and is the last African-American position player to be a full-time catcher on an MLB team’s 25-man roster. He achieved the rare feat of being drafted in the first round twice. He was selected in the 1989 MLB Draft’s first round directly out of high school as a draft-eligible senior by the Montreal Expos but decided to attend the University of Miami.

The newest team in the NL because of expansion, the Marlins organization used its first-ever draft pick to select Johnson in the first round of the 1992 MLB Draft. Johnson spent seven years in a Marlins uniform and also played for the Colorado Rockies, Baltimore Orioles, Tampa Bay Rays, Chicago White Sox, and Los Angeles Dodgers during his career. He is a cousin of Hall of Famer Fred McGriff and a nephew of longtime minor leaguer Terry McGriff.

Johnson made his MLB debut during the 1994 season, making a brief cameo in four games. He played in 97 games during his rookie season in 1995, becoming the fourth catcher to win the Gold Glove award during their first year in MLB history. He went .251/.351/.410 in 351 plate appearances with 15 doubles and 11 home runs, finishing seventh in the NL Rookie of the Year race.

He affirmed himself as one of the premier defensive catchers of the 1990s by winning four consecutive Gold Glove Awards. He was known for his ability to call games and throw out runners attempting to steal. The Florida native was one of the core pieces of the 1997 Florida Marlins team that won the World Series, logging 10 hits and a .844 OPS in the seven-game series versus Cleveland.

With a career slash line of .245/.330/.433, Johnson was more than competent in the batter’s box. His career wRC+ is a solid 97 and he logged a wRC+ north of 100 four times. He had his best offensive season in 2000, going .304/.379/.582 in 128 games with the Baltimore Orioles and Chicago White Sox.

Johnson appeared in two All-Star games during his 12-year career, amassing 1188 games played. He finished his career as an above-average defender and average hitter who showed flashes of dominance. He was billed as the hometown hero and he more than lived up to the expectations, helping the ball club that calls South Florida home secure its first World Series title.

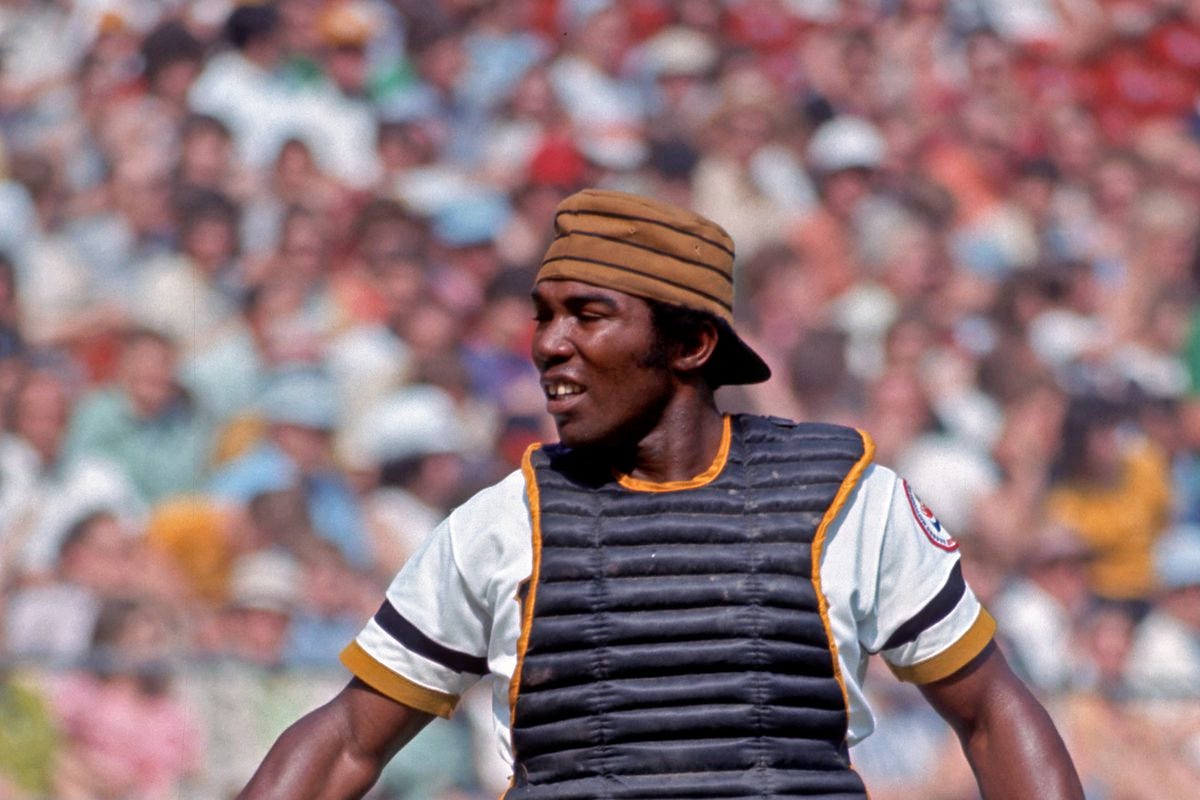

7. Manny Sanguillén

“The reality of a pitcher’s relationship with his catcher is that if he is on a roll, he is almost his own decision-maker… But Manny knew me just as much psychologically as the nuts and bolts of the actual pitch calling. And that is huge. And it comes with time…” - Steve Blass

Manny Sanguillén was one of the stars of a dominant and vibrant Pittsburgh Pirates team that appeared in six NLCS series and won two World Series during the 1970s. The Afro-Panamanian catcher was born and raised in Colón, Panama’s second-largest city. A three-time All-Star, Panama’s most significant backstop spent 12 of his 13 seasons wearing black and gold in Pittsburgh, his career spanning from 1967 to 1980. He spent one season as a member of the Oakland A’s in 1977.

He was scouted and signed by Pirates scout and fellow Panamanian Herb Raybourne, a legend also responsible for the careers of notable Panamanian Pirates players Omar Moreno and Rennie Stennett. Later in his career as a scout with the Yankees, Raybourne signed Hall of Famer Mariano Rivera.

“Sangy” was a top prospect during his time in the minor leagues but was always overshadowed by rival catcher Johnny Bench. This relationship carried over to the majors as they’d both debuted during the 1967 season for two rivals who would face each other in the playoffs four times during the 1970s.

Bench was the greatest catcher of their era by far and Sanguillén was somewhere in the second tier. The Reds were the National League’s best team during the 1970s with Pittsburgh in second place. Out of four head-to-head matchups for the National League Championship Series during the 70s, the Reds won three of them.

Sanguillén was an aggressive, free-swinging batter with generational bat-to-ball skills. He had a minuscule 6% career strikeout rate but the caveat was he virtually hit for no power during his career. 1173 of his 1500 total hits were singles. He posted a 296/.326/.398 career slash line across 5383 plate appearances in 1448 career games.

He had a career 99 wRC+, logging five seasons above 100. His peak offensive year was in 1975, batting .328/.391/.451 in 537 plate appearances. He was a competent and versatile hitter who slotted into a variety of different roles in a lineup. He spent a significant amount of his career batting second, fifth, sixth, and seventh.

He was an above-average defender behind the plate during his career. One of his main strengths was controlling the running game, owning a 39% career caught-stealing rate. His game-calling received great praise as well, catching a no-hitter during the 1969 season.

He had a great relationship and rapport with the pitching staff and the rest of the position players he played with throughout his career. His outgoing personality combined with his productivity on the field, bilingualism, and the position he played made him an important presence in a clubhouse that included Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente.

6. Elston Howard

“When Elston Howard died, The Yankees’ organization lost more class on the weekend than George Steinbrenner could buy in 10 years.” - Red Smith

Elston Howard was a catcher from St. Louis, Missouri who played professionally for 15 years. The first African-American to play for the New York Yankees, he was also traded from the Yankees to the Boston Red Sox. He is one of the few individuals to have only played for the Yankees and Red Sox during their MLB career. He is also one of the few who have played in a World Series while wearing both uniforms. He was a 12-time All-Star and won four World Series as a player with another two as a coach.

The St. Louis native was a star football and baseball player in high school, passing up numerous college scholarships to begin playing baseball professionally. He was primarily a left fielder and backup catcher with the Kansas City Monarchs, who sold him to the Yankees in July 1950. He spent the second half of 1950 playing in the New York Yankees farm system before serving in the U.S. Army for two years during the height of the Korean War, being based in Japan far away from combat because he was a professional baseball player.

The Yankees front office signed the young catcher intending to make him Yogi Berra’s heir apparent, carefully training him during his time in the minors. Longtime Yankees catcher Bill Dickey was his coach. They also worked vigorously at making him viable at other defensive positions due to the presence of the aforementioned Berra.

During his first five seasons, Howard played 178 games as a catcher out of 482 total defensive appearances. The majority of his time was logged in left field with some appearances at first base. Upon becoming the primary catcher before the 1960 season, Howard established himself as one of the most productive catchers in baseball both offensively and defensively. Howard has six seasons with a wRC+ above 100 and three seasons with more than 20 home runs. When compared to other catchers based on what they did with the bat from 1960 to 1970, he’s top five in runs scored, RBI, home runs, and total hits.

He was extremely effective at preventing runners from stealing bases, routinely winding up in the top 10 for caught stealing percentage during his career. He made very few errors even though he made a lot of defensive appearances during each season.

Howard’s magnum opus was the 1963 season when he won AL MVP and led the Yankees to their fourth of five straight World Series appearances from 1960 to 1965. He went .287/.342/.528 with 21 doubles and 28 home runs, also winning one of his two Gold Gloves.

He played in the 1948 Negro League World Series during his sole year as a Kansas City Monarch and appeared in 10 MLB World Series. Howard played in 9 World Series as a Yankee and made one appearance as a member of the Boston Red Sox. During his extensive postseason career, Howard played against a myriad of legendary Black talent in the World Series. He clashed with Jackie Robinson, Junior Gilliam, Roy Campanella, Henry Aaron, Roberto Clemente, Bob Gibson, and Willie Mays.

Explaining My List

I knew out of these five catchers, Elston Howard was the best and he was going to the the highest. When you look at his offensive/defensive peaks, the postseason success, and the length at which he was an above-average player his resume separates itself from the other four, respectfully.

Manny Sanguillén is one of the most underrated contact-oriented hitters of The Integration Era and an underrated piece of the Pirates teams of the 1970s. While he wasn’t a defensive stalwart or a dominant offensive player, he was above-average in both aspects of the game when compared to his peers behind the dish.

Trying to figure out whether I wanted John Roseboro or Earl Battey in the tenth slot was bothering me until the light bulb in my head exploded. Battey having extremely similar numbers and productivity to Roseboro despite far less playing time suggests he was the better player. When looking at the fact that Battey’s career was cut short by mismanagement and injury, adds further to the argument that he should be #9 and Roseboro should be #10.

John Roseboro was the most productive defensive catcher of his era and deserves to be rewarded for his durability as well. While he was not a great or even a good hitter, he also was not an outright offensive liability either.

Many people may be surprised at Charles Johnson being so low but honestly he failed to live up to his offensive potential. If Earl Battey’s career wasn’t so cut short by mismanagement and injury then he probably would be higher than Johnson as well.

Thank you Patrick, great stuff! I appreciate your efforts researching your subject and publishing your work🙂👍⚾️